I volunteered to participate in Career Day, at my daughter’s elementary school, and today was the big day. I thought long and hard about how to describe programming to fourth graders, without boring the crap out of them. As it happens, the three 25-minute sessions I did went very well. I thought I’d share my experiences, in case other geek parents find themselves in this situation.

Some of the kids signed up for my session, because they thought I was going to talk about programming video games. I told them that very few working computer programmers are actually video game programmers, just like very few people who play basketball actually end up in the NBA. “But,” I then said, “I’m going to try to show you that there are many different kinds of computer programming.”

First, I talked about computers, of course:

- how ginormous they were when I was their age

- how they usually resided special, air-conditioned rooms, all by themselves

- how people needed special badges just to get into those rooms and touch the computer

I pointed out that, because they were big and expensive, computers had more limited uses then, unlike today. I said that, today, computers are everywhere. At that point, I asked the kids to name places they knew used computers. I got the usual responses, such as:

- my house

- my Nintendo DS

- the grocery store

- the cash registers at the cafeteria

- Staples

I then pulled out my Droid phone and asked them if they knew what it was. They did, of course, though some mistook it for an iPhone. I asked if it was a computer, and we talked about that for a minute or so. I showed them the flashlight app for it and talked about how someone actually sat down and wrote a program to grab the camera’s flash and turn it on, and then put that program out on the web, for others to use.

Next came the iPad. We talked about how people use them. I showed them the calculator app, which is hilarious, because the calculator’s keys are so huge on the iPad. We talked about how the calculator keys change when you change the iPad’s orientation, and how someone actually wrote the program to do that.

Then I asked the kids to try to think of some other places we can find computers today, places you don’t normally think of finding computers. I asked them if there were any computers in their cars. Some kids mentioned the GPS, so I, “Right!”, and we talked briefly about how GPS units talk to satellites and use that information to show where you are on a map, and how some people actually wrote software to do all that.

Next, I decided to talk about anti-lock brakes. As it happens, the children had just finished a science unit on simple machines, so the concept of friction was still fresh in their minds.

“How many of you like to slide across a slippery floor in your socks?” I asked.

Loads of hands went up in the air.

“So, why does that work?” I responded. “What’s missing, that allows you to zip so fast across the floor?”

Inevitably, at least one child piped up, “Friction!”

“Yes! Could you walk on that floor without friction?”

“No!” came a chorus of responses.

“So, what happens when a car’s tires lose friction, say, on ice?”

“It skids!”

At this point, I told them how, when I was learning to drive, we were told to pump the brakes, which is kind of like skip-stepping on that slippery floor, to avoid sliding in your socks. This proved to be a very natural way to describe, in simple terms, how an anti-lock braking system uses its built-in computer to monitor the slippage of the wheels, how it pumps the brakes “really, really fast” when the car loses friction, how it doesn’t forget to do that (like we humans can)–and how someone had to write the anti-lock braking software.

In all three sessions, this little discussion resulted in lots of nodding heads, so, apparently, I hadn’t bored the crap out of them so far.

Then we talked a bit about how someone becomes a programmer. When I asked how that happened, they all said, “School,” or some variant. I wanted to get across how both book-learning and practical play-time were important, so I invoked science.

“Your teachers are teaching you science, right? So, part of that process is that they teach you things in class, and they give you homework to do, and they give you tests. But that’s only half of it, right? What’s the other half, the really fun half?”

Invariably, there was a least one kid who said, “Experiments!”

That not only gave me a chance to invoke Mythbusters (always good for an, “Oh, yeah!”), but it was a great analogy for describing how learning programming is also part book-learning and part playing.

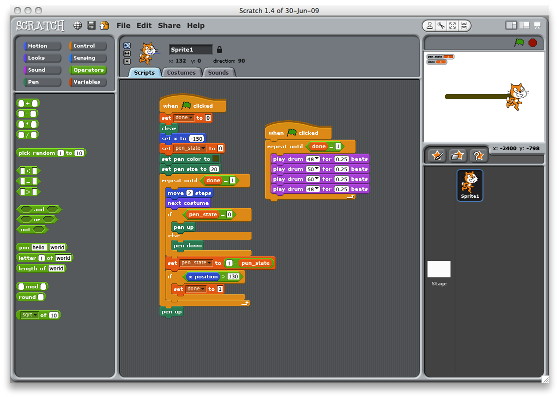

This was a perfect segué into the next part: A demo. I had found Scratch, a free, cross-platform programming environment that obviously has roots in Logo. But, Scratch is like Logo on steroids.

In Scratch, you write a program by dragging various widgets from tool bars onto the canvas, fitting them together like puzzle pieces. They drive a small screen, where you can add sprites, draw lines, and play music, among other things. A small Paint-like popup allows you to draw your own sprites, but you can also load prebuilt graphics. Widgets include:

- control structures (loops,

ifstatements, etc.) - sounds (drums, tones, and rests, with adjustable tempos and instruments)

- variables (though I skipped those for this short demo)

- pen-related widgets (“pen up”, “pen down”, “pen color”, etc.)

- movement widgets. (The set x,y widgets allowed me to tie the discussion into a recent math unit, for instance. But there are other movement widgets, like “walk n steps”.)

When you drag a control into the canvas, you can double click it, and that fragment runs immediately. Piece it together with others, and you can run them separately, too. Put them all together, and you have your program. By creating separate, disconnected pieces, you can get parts that run in parallel. Scratch even supports an event-driven model, allowing you to communicate between pieces of your program; this turns out to be the simplest way to build subroutines.

You get the idea.

So, I had the kids gather around behind me, I knelt on the floor in front of my laptop (which was on two spare kid desks), and we built a program.

First, we drew a simple sprite. Then, I showed them how to move the sprite across the screen. We tested that part. Then, we put that action into a loop, and ran that. (They didn’t know it, but they were obviously being introduced to incremental development.) Then, we added a snail trail, so the moving sprite left a purple line as he walked across the screen. (Funny: In all three sessions, when I asked the kids what color the line should be, they said, almost unanimously, “PURPLE!”) Finally, we modified the loop so that after every step, the sprite stopped briefly, and the program played two drum tones.

I had about 25 minutes per session, with about 12 kids per session. This talk format turned out to work really well with that time frame and that size. The kids were attentive during the talk, since I didn’t just lecture at them, but kept asking them questions. But they were positively rapt during the programming session. At the end, I told them, “Okay, you’re all now programmers,” which, of course, they loved. I also told them that if they’re interested in playing with Scratch, they could have their parents email me, and I’d tell them how to download it, “because the best way to decide whether programming is fun or sucky is to try it.”

I cannot praise Scratch enough. For this kind of talk, and for introducing children to programming concepts in a fun way, Scratch seems ideal. I ran it on my Mac, but it’ll run on Linux or Windows. It’s written primarily in Java, with a native executable front-end.

The best part about this whole experience, even better than finding Scratch, was how much fun I had. Most ten-year-old kids aren’t to the “I’m too snarky and cool for you adults” phase, yet, and they were attentive and engaged, even during the boring talky parts. I had a blast.

If you’re a geek and a parent, I highly recommend sharing your geekitude with your children and their friends. It’s rewarding as all hell.